Zimbabwe’s Judiciary

The Judiciary [sic] Service Commission, JSC has placed orders for 64 wigs made of horsehair from the exclusive and expensive Stanley Ley Legal Outfitters in England, according to a highly placed source in the JSC.

The price of wigs at the shop — established in 1903 in the Chancery Lane area of the City of London — ranges between Ksh.2,426,000 (US$2,426) and Ksh.327,400 (US$3,274,) each.

The JSC ordered 64 wigs at Ksh.242,600 (US$2,426) each costing a total of Ksh.15,528,600 (US$155,286).

Zimbabwe is currently going through tough economic times forcing Lloyd Msipa a Zimbabwean lawyer and political commentator based in London to term this is an extravagance.

Can’t the judges function without the wigs? Why spend thousands of dollars on those wigs when the people in the country have no food?

— Yvonne Dalitso Zulu🇿🇲 (@YvonneDalitso) April 4, 2019

What is the role of the wigs? Does one forget law without it? Does one pass incorrect judgement just because they are presiding over a case without wearing the wig?

— Nyota (@omuwiwomusolo) April 4, 2019

The wigs history is known to have originated from the British colonial periods. They left their wigs behind after colonizing Africa.

They are so old-fashioned and so uncomfortable, that even British barristers have stopped wearing them. But in former British colonies — Kenya, Zimbabwe, Ghana, Malawi and others — they live on, worn by judges and lawyers.

In Kenya, former chief justice Willy Mutunga appealed to remove the wigs from the courtroom, arguing that they were a foreign imposition, not a Kenyan tradition.

He swapped the traditional British red robes for “Kenyanized” green and yellow ones. He called the wigs “dreadful.”

But that outlook wasn’t shared by many Kenyan judges and lawyers, who saw the wigs and robes as their own uniforms, items that elevate a courtroom, despite — or because of — their colonial links.

“It was met with consternation from within the bench and the bar,” said Isaac Okero, president of the Law Society of Kenya.

Okero is a defender of the wig and the robe and argues that they represent more than a British tradition, but something that distinguishes the country’s judges.

“I don’t feel at all that it has any negative connotation of colonialism. It has risen beyond that. It is a tradition of the Kenyan bar,” he said.

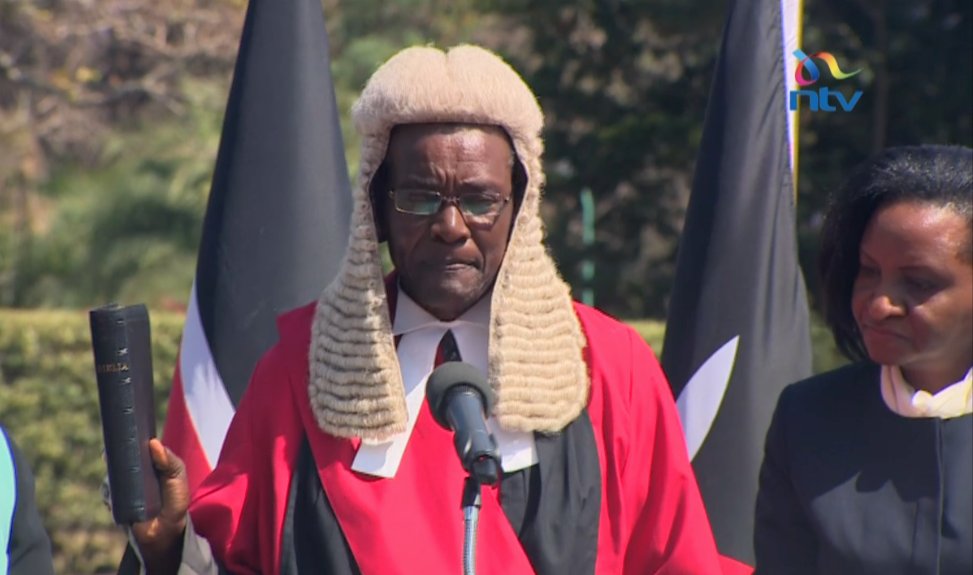

However, Kenya’s current chief justice, David Maraga, has indicated that he wants to revert to the colonial traditions. During his swearing-in ceremony, he wore a long white wig and the British-style red robe. Many Kenyans were perplexed.

The curly horsehair wigs have been used in court since the 1600s, during the reign of Charles II, when they became a symbol of the British judicial system.

Some historians say they were initially popularized by France’s King Louis XIV, who was trying to conceal his balding head.

By the 18th century, they were meant to distinguish judges and lawyers — and other members of the upper crust. Enter the word “bigwig” into the lexicon.

Other countries in the British Commonwealth, such as Australia and Canada, also inherited the wigs and robes but have moved toward removing them from courtrooms.

An Australian chief justice last year demanded that barristers remove their wigs before addressing her.

In Britain, the House of Commons recently lifted the requirement that clerks, who are experts in parliamentary law, wear wigs. John Bercow, the speaker, said the change would promote a “marginally less stuffy and forbidding image of this chamber.” But aside from the wigs, African courts have adapted to a post-colonial context.